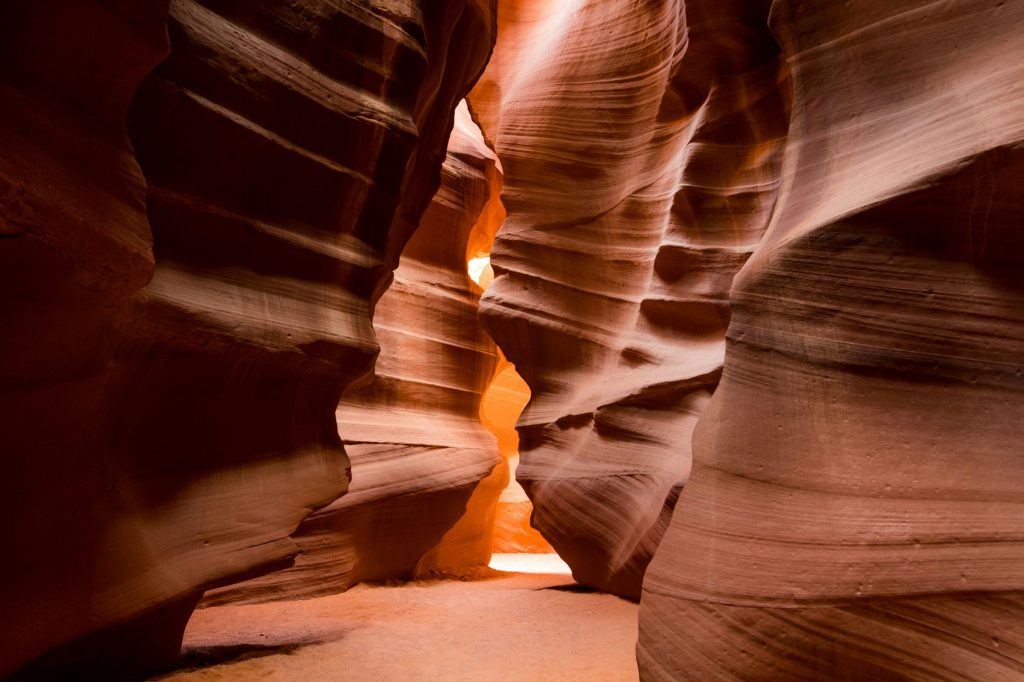

Anxiety has been my constant companion for years, a demon perched on my shoulder reminding me, especially when I relax, that I should not. A normal workday is spent occupied with tasks and interactions, a running to-do list so there is no time to think. Yet when my mind clears and a task is completed, anxiety tauntingly whispers in my ear, “Well, what about…?” My mind probes, until it eventually finds some event or circumstance – often one completely out of my control – to latch onto and be consumed by. It is as if I am gazing out over a landscape of leafy mountains surrounding a placid lake and wondering, “If I go near that water, I’m sure there will be snakes underneath.” Serenity feels like nothing but the pause before impact.

The level of discomfort ranges from mildly annoying to utterly debilitating. In extreme cases, anxiety can dominate my every waking – and even sleeping – hour, smothering my thoughts and leaving me completely anhedonic for days on end. There are moments I envy a random passersby: “Ah, look at their carefree existence – they are not weighted down by this anxiety.” My anxiety can become so extreme that I would gladly trade places with anyone in order to alleviate the suffering. I long for an escape – a vacation abroad, shut off from all familiar surroundings so that I have no association with the ghosts of my anxiety.

In my cursory Google searches on anxiety, I kept coming across the idea that our brains evolved to be hyper-alert to danger. The constant watchfulness was lifesaving back when humans roamed the savannas. Is that a lion hiding in the grass? Are there crocodiles beneath those calm river waters? Could those grey clouds portend a thunderstorm, flooding the stream and cutting me off from my family and clan? That same system can misfire in our modern world that is far less immediately dangerous.

In 2026, we don’t fear lions on the morning commute, yet the mindset shaped by those ancient dangers still lingers. The threats have changed from predators and the elements to work deadlines, personal interactions, political outcomes, and even distant wars that reach us through a screen, but the alarm system remains the same.

I’m told anxiety has many physiological side effects: your body releases the chemicals to enable you for “fight or flight” response so your muscles tense, your heart rate increases, and you can find it hard to breathe. My own body felt as if it was injected with a dark, toxic fluid that sheathed my innards, spreading inward and wrapping around my organs like a suffocating, oppressive layer. It dulled and agitated at the same time – a dense, uneasy presence that made it impossible to settle, as if my own physiology had turned quietly hostile.

Of course, some level of anxiety can be useful – in my work, I have to acknowledge that many outcomes are unpredictable. A dose of anxiety prepares me to be prepared. People who are good at what I do anticipate possible scenarios and prepare responses in advance.

Anxiety seeped into my routines, my sleep, even the architecture of my home. A random – and usually inconsequential – work-related piece of news on a Sunday night could drive me to sleep in the family room so I could monitor this development ahead of the workday without disrupting my partner. In my dreams I would sometimes see the resolution to a looming problem or the outcome I feared most, even pausing mid-dream to think, “My eyes are closed — I’m asleep — how can I be reading this?” I would wake to find the event had indeed unfolded, though almost always without consequence. All that dread had been for nothing.

And then there was the anxiety about the anxiety. Nights lying awake worrying about when the next wave of anxiety would hit. Stumbling to work in a daze, the fatigue I felt from such suffering was almost a relief – I was so tired I could only concentrate on finishing the tasks immediately in front of me and therefore had no time for anxiety.

Over the years, I’ve found that the most pernicious anxieties come not from anticipated events, but from the possibility of small obstructions. To return to the lake analogy, I might be rowing toward an island in the middle of the lake for a difficult negotiation, only to become consumed by the fear of snakes suddenly leaping into the boat. The stakes heighten the feeling because the course of a single day can ripple into my family’s future; that responsibility is simply part of what one signs up for in my profession.

Yet even as I’ve been active in my work and reasonably successful, managing anxiety remains a priority. If it wasn’t the fear of my firm’s collapse and the impoverishment of my family, my mind would simply redirect to another imagined catastrophe. It felt like living with a permanent anchor sunk into the sea floor – I could move, even build momentum, but never without resistance, never without the constant pull reminding me how easily everything could be dragged under. That unrelenting tether to dread was what finally pushed me to seek treatment.

As with many mental illnesses, recovery arrived in fragments – gradual, uneven, but real. To my surprise, the earliest relief came not from tools or strategies, though those would later prove essential, but from the simple act of entering therapy. After the first session – little more than a careful introduction – I felt lighter. I finally had somewhere to set the weight down. Why? I suddenly felt I had an outlet, a repository for my anxieties. An anxious thought would hit me and I could say, “Okay, I can hold on until the next session.” I began to imagine placing each worry into a mental box, something I could open later in the presence of someone equipped to help me face it.

At the same time, other activities suddenly acquired greater therapeutic significance. In a pure anxiety state, I could only bemoan the black clouds on the horizon and couldn’t appreciate the simple joys of leisure. Hobbies and otherwise pleasurable activities – playing guitar, going for a run, spending time with family, etc – could only provide limited relief: “Why bother with these trivialities when I’ve got this lion pride descending on my cave?”

Once I had set my course towards recovery, I was able to ascribe therapeutic attributes to these activities. Rather than self-flagellating neglect or encaged pleasure, I was able to recognise them as part of getting better. I became more present in conversations with family and friends, more patient with my co-workers and children, more able to inhabit the moment rather than brace for catastrophe.

With the help of mental health professionals, I was able to compartmentalise the components of my anxieties. Some could be eased by small, practical steps; others by calmly considering possible outcomes and accepting that not all of them were in my control. I learned to set the terms of engagement rather than letting anxiety dictate them. If I had prepared as thoroughly as I could, I allowed myself to step back from the endless rehearsal of what-ifs and to not feel agony if an eventuality did not go my way. If events did not unfold in my favour, I no longer treated that as catastrophe, but as part of the uncertain terrain of being alive, not a verdict on my worth or the shape of my future.